Introduction

Although edema can result from a variety of conditions, medications or other contributing factors, it is now understood that all edema is lymphedema through a spectrum of lymphatic insufficiency.1 This article will highlight the latest evidence supporting this paradigm shift by looking at the new understanding of hemodynamics at the Endothelial Glycocalyx Layer, and the associated links between the lymphatic and integumentary systems. Further, it will explain how this information is relevant to clinical practice to help you differentially diagnose and manage lower extremity edema.

New lymphedema paradigm

One of the most significant recent changes regarding lymphedema is a more refined explanation of fluid hemodynamics impacting our historical understanding of Starling’s Law. Previously, it was thought that 90% of fluid moving from the blood to the interstitium was reabsorbed back into the venous end of the capillary, yet the lymphatic system was only responsible for managing 10% of the fluid load. The new paradigm of the Endothelial Glycocalyx Layer (EGL) as the gatekeeper of fluid filtration from blood capillaries explains how there is only diminishing net fluid filtration across the blood capillary bed and no reabsorption at the venous end; 100% of all interstitial fluid is reabsorbed by the lymphatic capillaries alone during homeostasis. 2-3

Acting as a complex molecular sieve, the EGL precisely regulates fluid and protein movement through the capillary wall into the tissues.4-6 Conversely, the EGL also prevents movement of proteins and fluid back into the venous side of the capillaries, even when interstitial hydrostatic pressure is increased, or tissue oncotic pressures remain higher within the blood capillaries. Thus, all fluid and proteins exiting the blood capillaries must be removed from the interstitium by the lymphatic capillaries alone. This has led to the new understanding that all edemas are on a lymphedema continuum and represent relative lymphatic insufficiency or failure. 1,7 The system is either temporarily overwhelmed (transient lymphedema/dynamic insufficiency) or the system is abnormally developed, damaged or permanently impaired leading to the disease of chronic lymphedema (mechanical lymphatic failure).

Lymphedema pathophysiology

The lymphatic system is analogous to the body’s sewer or recycling system. It is responsible for maintaining fluid homeostasis by managing interstitial fluid and mobilizing waste products (proteins, senescent cells, macromolecules, etc.). The lymphatic system is also tasked with the absorption and transportation of lipids and fatty acids to the circulatory system, and transporting antigens, antigen-presenting cells and other immune cells to the lymph nodes where adaptive immunity is stimulated. Collectively, all components within the fluid transported by the lymphatic system are called the “lymphatic load”.9

Pathophysiologically, chronic lymphatic dysfunction or failure presents unique changes affecting the integumentary system. When the lymphatic load is not readily reabsorbed by the lymphatic system from the interstitial tissues, a pathohistological state of chronic inflammation results. Free radicals trapped in the tissues denature proteins and oxidize cell membranes attracting monocytes to the area that differentiate into macrophages. These macrophages take in proteins through pinocytosis, which activates the macrophages to release cytokines. This, in turn, activates fibroblasts, which are stimulated to produce excess collagen.8,9 Excess collagen formation causes connective tissue proliferation and fibrosis resulting in the thickened, fibrotic skin and wart-like projections (papillomatosis and verrucous) commonly seen with chronic lymphedema.10 Additionally, other fibroblasts differentiate into adipocytes.9 If treatment is not implemented, the chronic inflammatory process persists and the clinical presentation eventually can result in enlargement of the body part, thickened and fibrotic dermal and subcutaneous tissues, and other significant integumentary changes.11

Disorders of the lymph system, whether systemic (macro-lymphedema) or localized (micro-lymphedema), produce cutaneous regions susceptible to infection, inflammation and carcinogenesis.10,12-13 The inter-relationship of the lymphatic and integumentary systems is starting to become more readily appreciated as a functional lymphatic system is essential to an organism’s overall health given its role in fluid homeostasis, removal of cellular debris and mediating immunity and inflammation.14 The chronic inflammation resulting from lymphedema creates a region of cutaneous immune deficiency or a localized skin barrier failure. The associated abnormalities are called lymphostatic dermopathy, which is the failure of the skin as an immune organ.10,12-13 Because of this, alterations in skin integrity, recurrent infections (commonly cellulitis), venous dermatitis, diminished wound healing, various dermatological conditions, and even skin malignancies become more prevalent highlighting the inter-connectedness of the lymphatic and integumentary systems.10,12-13 Impairment or dysfunction in one system leads to associated complications in the other.

Edema/lymphedema examination

In combination with a comprehensive medical history and medical workup, a physical exam of the edema and its characteristics is essential. This exam should include the following simple tests. First, observe the extremity for subtle changes in contours indicative of edema and note any associated skin changes. Listen to the patient. Often, they will feel a heaviness or fullness in their limb before noticeable clinical signs. Next, cradle and gently palpate the limb circumferentially as you slowly move up from the toes or fingers to the groin or shoulder. Manually identify areas that feel full, taught, edematous or fibrotic. Next, perform the Bjork Bow Tie Test in these areas.

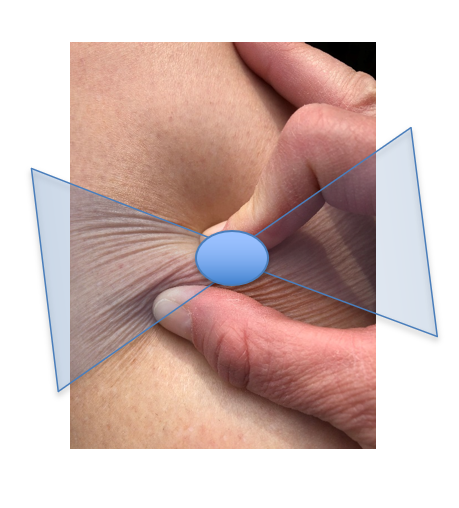

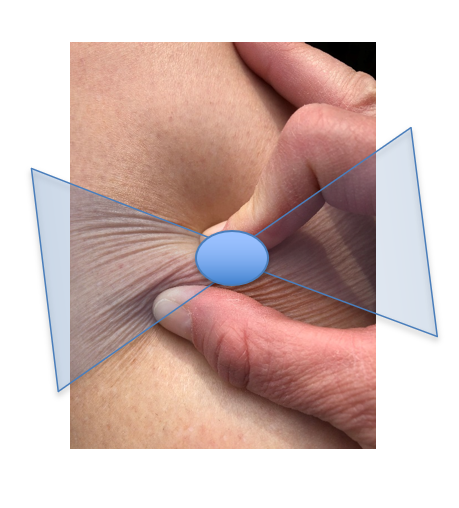

The Bjork Bow Tie Test is an expanded version of the Stemmer’s Test.15,16 The Stemmer’s Test is performed by pinching the skin at the base of the second toe or middle finger.17 If the skin can be lifted and pinched, the test is negative. A negative test does not exclude lymphedema. Thickened skin with fibrotic soft tissue changes will not lift and approximate when pinched and thus produce a positive test. The Stemmer’s Test is never falsely positive and leads to a definitive diagnosis of lymphedema.9,17 However, a limitation of the Stemmer’s Test is that, by definition, it is to be performed on the toe or finger only. And, based on the new paradigms of the microcirculation and definitions of lymphedema, all swelling can technically be diagnosed as lymphedema. The question is, what type of treatment intervention should follow? Thus, the Bjork Bow Tie Test was developed to expand the application of a Stemmer’s type test to any area of the body, as well as identify soft tissue changes, such as fibrotic tissue, that may warrant interventions to help remodel the soft tissue back to a normalized state.15,16

Unlike past perceptions of lymphedema presenting as gross swelling, marked fibrotic soft tissue changes or disfigurement, the subtle dermal changes are most important in early diagnosis and recommendations for care. To perform the Bjork Bow Tie Test, in one maneuver, gently pinch, roll and twist the skin between the thumb and pointer finger, noting the quality of tissue texture and thickness. Healthy skin can be lifted and pinched, should feel slippery between the layers when rolled, and produce a “bow-tie” of wrinkles when twisted. Skin that tests positive will be thickened, less pliable, less able to be pinched and lifted, more difficult to twist, and produce limited “Bow Tie” of wrinkles. A positive test indicates signs of thickening and fibrotic tissue texture changes as a result of lymphedema-induced chronic inflammation. Figure 1 demonstrates how to perform the Bjork Bow Tie Test and the difference between a negative and a positive test.

In addition to tissue texture changes, circumferences or girth can be measured using a cloth tape measure. For more precise measurement, new scanning technologies are emerging that scan a limb within minutes using an iPhone or iPad interface, create a 3-D avatar of the limb, as well as calculate volumes.18 In addition, breast and truncal edema can be measured and quantified using a hand-held, pocket-sized moisture meter that objectively measures the moisture content of affected versus unaffected areas.19 This can assist in objectively identifying areas of lymphedema that are often subtle or subclinical.

Lymphedema diagnosis

According to the new microcirculation paradigm, all patients presenting with swelling do in fact have lymphedema to some degree. The lymphatic system may be overwhelmed resulting in transient lymphedema (i.e., ankle sprain, CHF) or the system may be damaged leading to the disease of lymphedema. Even when no swelling is present, risk factors may be identified leading to a Stage 0 lymphedema diagnosis of subclinical lymphedema.17 Table 1 lists many of the risk factors and co-morbidities contributing to lymphedema. Early identification and intervention are key, and the contributing factors and underlying comorbidities must be addressed through comprehensive medical management in order to achieve the best patient outcomes. Utilizing the components of Complete Decongestive Therapy in the context of the patient’s entire medical picture will allow for safe and effective treatment. The authors are now referring to this management as Lymphatic and Integumentary Rehabilitation.

In the United States, the most common cause of lymphedema in the upper extremities is breast cancer20 and in the lower extremities, chronic venous disease is the most important predictor for the development of lymphedema.21 With respect to obesity, lymphatic dysfunction can occur with a body mass index greater than 50, and lymphedema may be universal in patients with a BMI greater than 6018. Various other contributing co-morbidities and co-factors may lead to lymphedema, and most clinical presentations of lymphedema are resulting from a combination of approximately seven co-morbidities.22 Data from the Canadian LIMPRINT study showed that the most common underlying cause of lymphedema in an outpatient wound clinic was venous disease, 72% of patients had a history of cellulitis, and almost 40% had an open wound.23

Conclusion

Edema is a common and prevalent condition presenting clinically from mild to severe. Looking at the presentation and quality of the edema, its characteristics (turgor, texture, pitting/non-pitting), associated integumentary findings, combined with a comprehensive medical review of the patient will help in determining where on the lymphedema continuum the patient resides. Many edemas are transient, due to lymphatic insufficiency, which should fully resolve with proper medical management once the underlying cause or contributing factors have been identified and modified. For chronic lymphedema due to lymphatic failure, managing the underlying medical issues in combination with Complete Decongestive Therapy will help the patient manage this life-long disease.

Table 1: Lymphedema risk factors

Adapted from Framework L. Best practice for the management of lymphoedema. International consensus. London: MEP Ltd. 2006:3-52.

- Chronic venous insufficiency

- Post-thrombotic syndrome

- Vein stripping or harvesting

- Surgery (i.e. revascularization, TKA, THA, abdominal surgery, hysterectomy)

- Decreased mobility (aging, CVA, TBI, SCI, immobilization, etc.)

- Obesity

- Congestive heart failure

- Chronic kidney disease

- Trauma

- Scars

- Burns

- Lymph node dissection or removal

- Radiation

- Chronic wounds

- Recurrent cellulitis

- Congenital malformation of lymphatic vasculature

- Tumors obstructing lymphatics

- Travel or living in Lymphatic Filariasis endemic areas

- The prolonged dependency of the limb or other body parts

- Hyperthyroidism

- Medications with edema as a side effect

- Chronic skin disorders and inflammation

- Arteriovenous shunt

Figure 1: Bjork Bow Tie Test

Negative Bjork Bow Tie Test

Used with permission, courtesy Robyn Bjork

Positive Bjork Bow Tie Test

Used with permission, courtesy Suzie Ehmann

“Bow Tie” of wrinkles in Negative Test

Used with permission, courtesy Robyn Bjork

Heather Hettrick PT, Ph.D., CWS, CLT-LANA, CLWT, CORE is a Professor in the Physical Therapy Program at Nova Southeastern University in Florida. As a physical therapist, her expertise resides in integumentary dysfunction where she holds four board certifications/credentials. She is actively involved with numerous professional organizations, speaks on the national and international circuit, and is faculty and Director of Wound Education at the International Lymphedema & Wound Training Institute.

Robyn Bjork, MPT, CWS, CLT-LANA, CLWT is Founder and President of the International Lymphedema & Wound Training Institute. She is a Physical Therapist who holds multiple board certifications in wound and edema/lymphedema management. Bjork is a featured speaker at national & international conferences and is dedicated to the advancement of Lymphatic & Integumentary Rehabilitation.

References

- Mortimer PS, Rockson SG. New developments in clinical aspects of lymphatic disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014 Mar 3;124(3):915-21.

- Bjork R, and Hettrick H. Endothelial glycocalyx layer and interdependence of lymphatic and integumentary systems. Wounds International. 2018; Vol 9 Issue 2:50-55.

- Levick JR, Michel CC. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovascular research. 2010 Mar 3;87(2):198-210.

- Reitsma, S., Slaaf, D.W., Vink, H., Van Zandvoort, M.A. and Oude Egbrink, M.G., 2007. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, 454(3), pp.345-359.

- Weinbaum, S., Tarbell, J.M. and Damiano, E.R., 2007. The structure and function of the endothelial glycocalyx layer. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng., 9, pp.121-167.

- Woodcock, T.E. and Woodcock, T.M., 2012. Revised Starling equation and the glycocalyx model of transvascular fluid exchange: an improved paradigm for prescribing intravenous fluid therapy. British journal of anaesthesia, 108(3), pp.384-394.

- Bjork R, and Hettrick H. Emerging Paradigms Integrating the Lymphatic and Integumentary Systems: Clinical Implications. Wound Care and Hyberbaric Medicine. 2018; Vol 9 Issue 2:15-21.

- Scelsi R, Scelsi L, Cortinovis R, Poggi P. Morphological changes of dermal blood and lymphatic vessels in chronic venous insufficiency of the leg. International angiology: a journal of the International Union of Angiology. 1994; 13(4):308-311.

- Földi M, Földi E, Strößenreuther R, Kubik S, editors. Földi's textbook of lymphology: for physicians and lymphedema therapists. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012 Feb 21.

- Carlson A. Lymphedema and subclinical lymphostasis (microlymphedema) facilitate cutaneous infection, inflammatory dermatoses, and neoplasia: A locus minoris resistentiae. Clinics in Dermatology. 2014;32: 599-615.

- Shoman H, Ellahham S. Lymphedema: a mini-review on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Vasc Dis Ther. 2017;2(3):1-2. DOI: 10.15761/VDT.1000124

- Ruocco E, Puca RV, Brunetti G, et al. Lymphedematous areas: Privileged sites for tumors, infections, and immune disorders. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:662.

- Ruocco V, Schwartz RA, Ruocco E. Lymphedema: An immunologically vulnerable site for the development of neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:124-127.

- Ridner SH. Pathophysiology of lymphedema. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:4-11.

- Bjork R, Ehmann S. STRIDE Professional Guide to Compression Garment Selection for the Lower Extremity. Journal of Wound Care. 2019 Jun 1;28(Sup6a):1-44.

- Bjork R, Hettrick H. Emerging Paradigms Integrating the Lymphatic and Integumentary Systems: Clinical Implications. Wound Care and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2018;9(2):17-23.

- Framework L. Best practice for the management of lymphoedema. International consensus. London: MEP Ltd. 2006:3-52.

- Greene A. Diagnosis and Management of Obesity-Inducted Lymphedema. Plastic Recon Surgery. 2016 July;138(1):111e-118e.

- Greenhowe J, Stephen C, McClymont L, Munnoch DA. Breast oedema following free flap breast reconstruction. The Breast. 2017 Aug 1;34:73-6.

- Rockson S. Diseases of the Lymphatic Circulation in Vascular Medicine: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease, the 2nd Edition. Elsevier;2013:697-708.

- Mortimer P, Rockson S. New developments in clinical aspects of lymphatic disease. J Clin Invest. 2014 Mar;124(3):915-21.

- Wang W, Keast DH. Prevalence and characteristics of lymphoedema at a wound-care clinic. Journal of wound care. 2016 Apr 1;25(Sup4): S11-5.

- Keast DH, Moffatt C, Janmohammad J. Lymphedema IMpact and PRevalence INTernational (LIMPRINT) study: the Canadian data. Lymphatic Research and Biology. 2019 Mar 10.

Candice Cotton, RN, MSN, CWON, is a registered nurse who earned her BSN from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama, and her MSN from the University of Phoenix, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Cotton retired from the United States Public Health Service as a commissioned officer in 2011. She has worked in various clinical settings and served her last 16 years in PHS as a certified wound/ostomy nurse assigned to Navajo Area Indian Health Service, in Gallup, New Mexico. Currently, Cotton is working part-time as a wound/ostomy specialist at Huntsville Health Care Systems in their outpatient wound/ostomy clinic in Huntsville, Alabama.

Candice Cotton, RN, MSN, CWON, is a registered nurse who earned her BSN from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama, and her MSN from the University of Phoenix, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Cotton retired from the United States Public Health Service as a commissioned officer in 2011. She has worked in various clinical settings and served her last 16 years in PHS as a certified wound/ostomy nurse assigned to Navajo Area Indian Health Service, in Gallup, New Mexico. Currently, Cotton is working part-time as a wound/ostomy specialist at Huntsville Health Care Systems in their outpatient wound/ostomy clinic in Huntsville, Alabama.

“Before you heal someone, ask him if he’s willing to give up the things that make him sick.” — Hippocrates

“Before you heal someone, ask him if he’s willing to give up the things that make him sick.” — Hippocrates Non-compliant patients can be difficult. Have you ever been in the position where you know you are doing everything you should be, but your patient isn’t getting better? At one time or another, we have all been there, with a non-healing wound, wondering what vital aspect of the wound care process we are forgetting. Then we find out that our patients severely misunderstood our instructions, or even worse, ignored them. It has been estimated that the direct and indirect costs of non-compliance on healthcare are upwards of $100 billion per year. I would like to believe that most of my patient’s non-compliance is not because they are lazy or don’t care, but rather that I need to change my approach. Let me explain how we, as health care providers, can change our approach to improve compliance and patient outcomes.

Non-compliant patients can be difficult. Have you ever been in the position where you know you are doing everything you should be, but your patient isn’t getting better? At one time or another, we have all been there, with a non-healing wound, wondering what vital aspect of the wound care process we are forgetting. Then we find out that our patients severely misunderstood our instructions, or even worse, ignored them. It has been estimated that the direct and indirect costs of non-compliance on healthcare are upwards of $100 billion per year. I would like to believe that most of my patient’s non-compliance is not because they are lazy or don’t care, but rather that I need to change my approach. Let me explain how we, as health care providers, can change our approach to improve compliance and patient outcomes.